The role of the bladder is to store urine, which is liquid waste made by the kidneys and then carried to the bladder through tubes called ureters. During urination, muscles in the wall of bladder contract to force urine out of the bladder through the urethra.

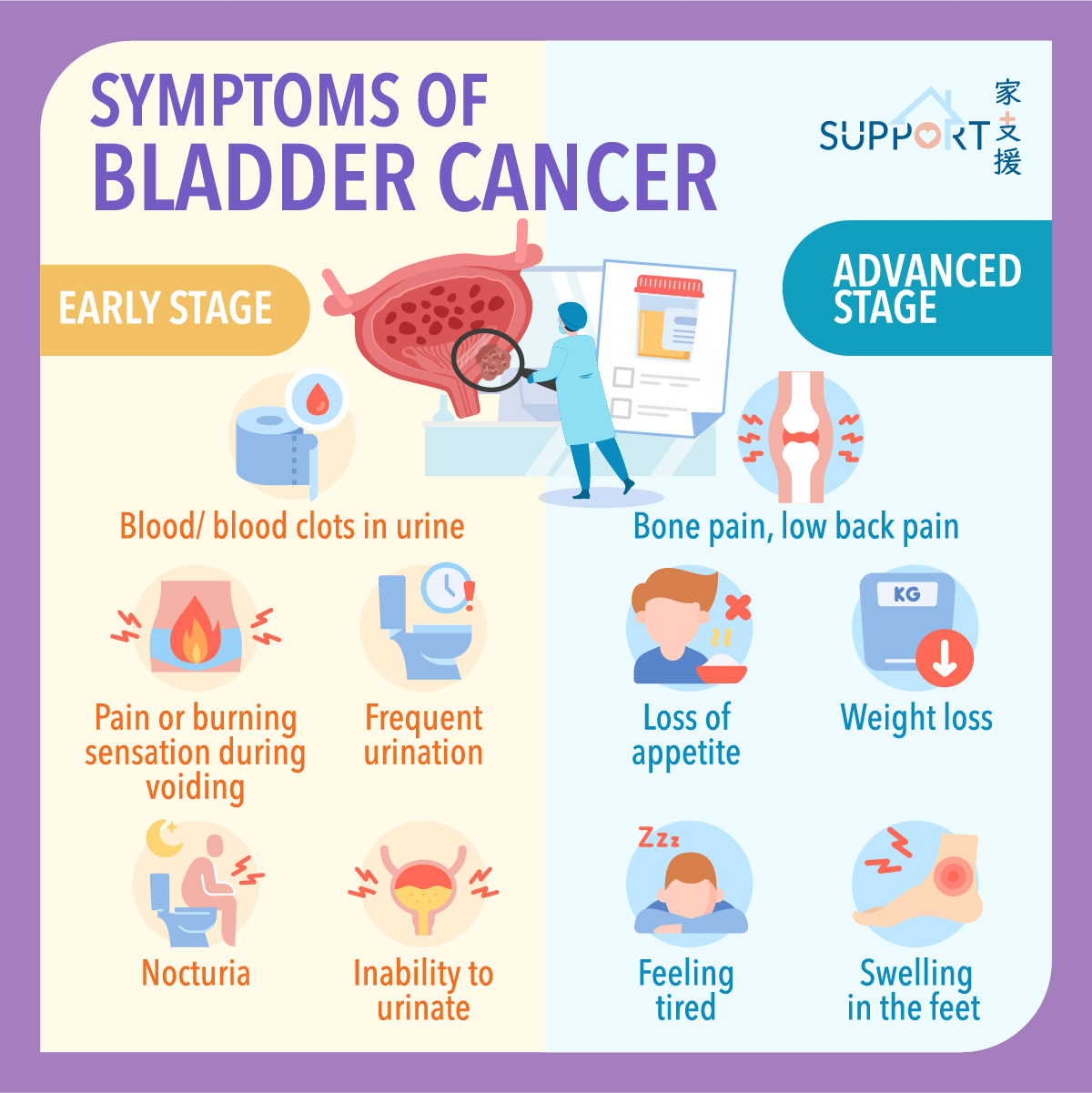

Most bladder cancers start in the innermost lining of the bladder, which is known as the urothelium or transitional epithelium. As the malignant tumour cells grow uncontrollably, they can invade into deeper layers of the bladder wall and muscles. Over time, the cancer might grow outside the bladder and spread to nearby lymph nodes, or to other parts of the body, such as bones, lungs, and liver.

Bladder cancer can be classified into different types, namely urothelial carcinoma (also known as transitional cell carcinoma), squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, small cell carcinoma, and sarcoma. Urothelial carcinoma is by far the most common type of bladder cancer, accounting for approximately 90% of the cases.

Key statistics for bladder cancer in Hong Kong

According to the Hong Kong Cancer Registry of Hospital Authority, there were 439 new cases of bladder cancer in 2022. The crude incidence rate of bladder cancer was 6 per 100,000 persons. Bladder cancer is more common in the age group of 55-70 and is three times more likely in men than in women. In 2022, there were 199 deaths from bladder cancer in Hong Kong. The crude morality rate was 2.7 per 100,000 persons. The highest death rate was noted in the age group of above 65.